The Case

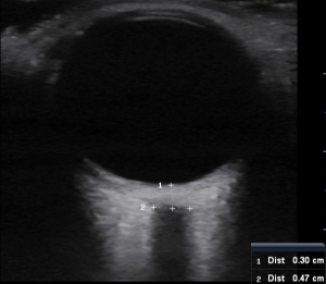

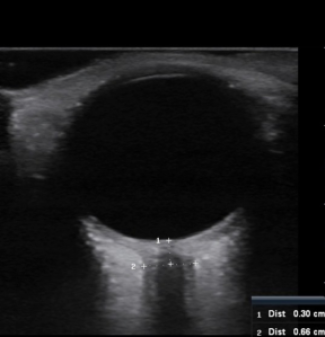

Generally, I like to write about positive ultrasound cases. This is not one of those cases. But out of this sad case there was much learning to be had for this med student. At the time of the case, I was on an emergency ultrasound elective. And I couldn’t have be happier! I was learning all sorts of awesome and useful skills. Another perk of being on ultrasound duty was that I got to tag along on all the ultrasound cases I can get my hands on, including the traumas (a big perk in my book). As soon as I heard a trauma called in, I gowned up, gloved up, goggled up, and masked up. I observed the FAST exam (Focused Abdominal Scan for Trauma) and helped however I was instructed. Mostly squeezing IV bags or fetching things, but I was in there; I had a job; and I was learning ultrasound awesomeness. Life was good…. like really, really good. Until it wasn’t. Enter a teenager in an ATV accident. One paramedic cranks out compressions, while the other relays patient information. Car versus ATV. Trouble intubating. And he’s asystolic. Huge bummer. This is not going to be fun and someone somewhere is going to be very sad tonight. Everyone is hustling. I stand at the foot of the bed squeezing fluids into the kid while lines are placed, drugs are pushed, and they figure out what’s wrong. I watch the FAST exam. Looks negative to me, so no visible blood in the pelvis, abdomen, or around the heart. Unfortunately the ultrasound’s heart view also shows no heart movement. There is no electrical activity on the ECG. He’s been down for a long time. Time of death is called. Everyone puts down what they were doing and steps away. I feel heavy. After the room has cleared, the ultrasound attending pulls the ultrasound up to the bedside. There is a valuable teaching opportunity here. He does another FAST exam, explaining it as he goes. Still no free fluid in the pelvis, abdomen, or pericardium. He puts the probe on his chest. No signs of pneumo or hemothorax. This is weird; an ATV versus car with no major bleeding from the neck down. I’m supposed to be learning what an ultrasound exam looks like on a trauma patient, but so far it all looks pretty normal. That’s odd… so what killed this kid? The ultrasound attending agrees it’s unusual and wants to check one more thing. Here’s where things get interesting. The only visible trauma is from the neck up; some bleeding from the ears, eyes, and an open scalp lac. With no helmet that really isn’t a surprise. What is a surprise is the ultrasound attending putting the ultrasound probe on his eye. What are we suppose to tell from this..? Intracranial pressure. Mind blow. Now I’m pretty sure the ultrasound attending is a wizard. On the screen, we see a normal globe with a huge optic nerve and sheath exiting. Before he even measures it, he can tell it’s too big. He measures it and confirms ICP is elevated. So how’d he do this?

Measuring Intracranial Pressure Using Ocular Ultrasound

In a Nutshell

- If you suspect elevated intracranial pressure (ICP), ocular ultrasound is a fast and easy method to detect it.

- You can measure the optic nerve sheath diameter (ONSD) using ultrasound.ONSD > 5 mm may indicate an ICP > 20 mmHg, especially in symptomatic patients.

- Not everyone with ONSD > 5 mm has elevated ICP.

- ONSD > 5.7 mm indicates an ICP > 20 mmHg.

- All patients with ONSD > 5.7 mm have elevated ICP.